Private investment in transmission – concessions (part 1)

April 27, 2022

By Ryan Ketchum and Chris Flavin. Ryan is a partner at Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP. Chris is Head of Business Development at Gridworks Development Partners, a development and investment platform principally targeting equity investments in transmission, distribution and off-grid electricity in Africa.

The first article in this series discussed the need to increase the level of investment in electricity transmission systems to reduce costs, facilitate the transition to energy systems that are less carbon intensive, increase system stability, and reduce the level of generation reserves that are required to maintain system stability. It also briefly introduced four business models that can be used to unlock new sources of capital by facilitating private investment in transmission infrastructure across most of Africa (and in emerging markets more generally). Those four business models are:

- whole of network concessions,

- independent transmission projects (“ITPs”), which are also known as independent power transmission projects,

- privatizations (a sale of shares by a government in a state owned utility or transmission company), and

- merchant lines.

Subsequent articles in the series discussed ITPs in further detail. In this article, we will examine whole of network concessions, including the circumstances in which a whole of network concession may be attractive to both host countries and investors and some of the challenges that are typically encountered in structuring these transactions.

Overview

A concession is a right to develop, construct, operate and maintain an infrastructure project and to earn profits paid from a share of the revenues generated by the project. Concessions are typically granted by a government, public authority, or state owned enterprise. A concession may be granted pursuant to a concession agreement, a lease, a lease and assignment agreement, a project development agreement, or similar agreement. In most countries, the name of the agreement that grants the concession is not important. Instead, the rights and obligations created are the defining features of a concession. Although the name of the agreement is not important, we will refer to it as the concession agreement.

A concession may be appropriate if a host country desires to:

- leverage the experience and know-how of the private sector to improve the performance of a transmission utility;

- increase budget certainty by transferring the responsibility for financing capital expenses from the public sector to the private sector;

- reduce the risks borne by the public sector by transferring responsibility for the development, financing, and construction of projects that are required to expand, reinforce, and upgrade the transmission system; and

- use private capital to finance significant improvements to, or significant expansions of, a transmission system, while retaining ultimate ownership over the transmission system and the ability to terminate the concession if the concessionaire fails to perform its obligations under the concession agreement.

A concession may be less attractive to a host country that:

- has an existing transmission utility whose performance equals or exceeds international benchmarks;

- is able to raise funding on suitable terms (either based on the balance sheet of the existing transmission utility or though public resources) to fund any network investment required; or

- is mainly interested in raising financing for a discrete transmission project or a package of discrete transmission projects (which may be achieved more quickly and efficiently using other models such as the IPT model).

Although there are a number of whole of network concessions over unbundled electricity distribution companies in Africa, the authors are not aware of a transmission company that has been the subject of a concession save for in Cameroon where a combined transmission and distribution concession was granted in 2001 before transmission was taken back into state control in 2021. Given the very significant funding required to expand the transmission networks in many African countries to meet energy access targets and transition to an increased share of renewable energy in the generation mix, it is likely that this form of private sector participation will be used in some markets in the foreseeable future.

A whole of network concession would be a significant change to a sector if implemented in most countries. If a government considers that a concession is an appropriate tool for achieving its objectives, it will also need to consider how the role of electricity sector participants will be changed by the concession, how stakeholders will be affected, and how to engage with those stakeholders to build support for the transaction.

Enabling environment

Network industries require ongoing investment. As a result, even a concession over of a transmission system that does not require significant expansion will require the concessionaire to incur capital expenditures to replace worn-out equipment, restore and refurbish existing equipment, and upgrade the transmission system as a whole over the term of the concession. In most African jurisdictions, it is likely that a concessionaire will be required to commit significant funds to expand the transmission network over the course of the concession to meet energy access targets. As a result, the rates that are charged by a concessionaire for transmission service cannot be set and fixed at the beginning of the concession.

Instead of establishing rates for the term of the concession at the outset, one of two approaches is usually adopted. The most common approach is for a concessionaire to be subject to technical and economic regulation by an independent regulator. The regulatory approaches regulators use to regulate utilities generally, and concessions in particular, will be covered in a separate article. These approaches require that a regulator articulate the methodologies it intends to use to regulate the concession in a set of tariff guidelines or a tariff methodology.

In the alternative, a government support agreement or concession agreement may include an annex that describes a regulatory methodology in essentially the same terms in which a set of tariff guidelines or a tariff methodology would describe it. The parties to the government support agreement (the host country and the concessionaire) or the concession agreement (the state owned transmission utility and the concessionaire) will then be responsible for applying the regulatory methodology following the terms of the contract. If and when an independent regulator is established, that regulator can play a significant role in applying the regulatory methodology if the government support agreement and concession agreement contemplate that outcome. This system is known as regulation by contract.1

Regulation by contract is more likely to be used in a market where there is insufficient regulatory capacity at the point when a concession is granted. Regulatory risk (including lack of regulatory track record) will be a key factor for investors in deciding whether they can support a transmission concession, and the level of returns that they will require. The returns required by an investor (often described as the cost of capital) have an impact on end user tariffs and it is therefore normally in both the government’s and the investor’s interests to reduce regulatory and tariff based risks as much as possible.

Legislative frameworks will very from country to country, and as described above, there are a number of legal forms that a concession can take. However, it is often the case that the legislative framework and other aspects of the enabling environment in which a concession will be implemented would include:

- an Act (such as a Public-Private Partnership Act) that (i) establishes the framework under which public-private partnerships are studied, structured, and awarded, (and (ii) clearly defines the role of contracting authorities and the government in structuring and awarding public-private partnerships;

- clear authority for the government, the sector regulator, or the state owned transmission utility to award a concession over the transmission assets;

- an independent regulator which issues licenses to utilities that operate in the electricity sector and regulates those utilities;

- utilities that have already been functionally unbundled into generation, transmission, and distribution (as opposed to a single vertically integrated utility);

- independent power projects (which will have given the host country, the regulator and other sector participants experience with private sector participation in the electricity sector); and

- clearly defined roles for generation, transmission, and distribution and clearly defined codes that govern their conduct and establish technical standards (such as a grid code, a distribution code, and a dispatch code).

However, as the discussion above as to how to use regulation by contract to achieve the seemingly impossible task of implementing economic regulation in a country that has not established an independent regulator shows, with enough creativity, a sector that lacks some of the above features of an enabling environment can still implement the concession model.

Contractual structure

In a typical transmission concession, a state owned utility that owns a transmission system (the “grantor”) grants a concession over its transmission network to a project company established by the investors to act as the holder of the concession (the “concessionaire”). At the same time, the ministry that is responsible for overseeing the electricity sector, or the regulator, grants a transmission license to the concessionaire. In addition, the host country may enter into a government support agreement, implementation agreement, or similar agreement (a “government support agreement”) with the concessionaire to provide certain identified types of support to the transaction.

Collectively, the concession agreement and the transmission license typically provide that:

- the grantor will retain ownership of the existing transmission system and lease the existing transmission system and related assets to the concessionaire;

- the grantor utility will lease or sell to the concessionaire all of the state owned transmission utility’s moveable property, equipment, and inventory of spare parts;

- the grantor will transfer some of the contracts to which it is a party – which may include on-going service contracts, contracts for the supply of goods and equipment, and contracts for the construction or supply of new assets that will become a part of the transmission system – to the concessionaire;

- the concessionaire will pay a concession fee, which may be structured as a one-time payment, on-going payments, or a combination thereof;

- the concessionaire will use the leased assets and the transferred assets to provide transmission service within the service territory described in the transmission license;

- the concessionaire will improve, repair, operate and maintain the transmission system;

- the concessionaire will expand, reinforce, and upgrade the transmission system to the extent required to provide transmission service within the service territory, and to the extent that expansion projects are approved by the regulator in accordance with the tariff guidelines.

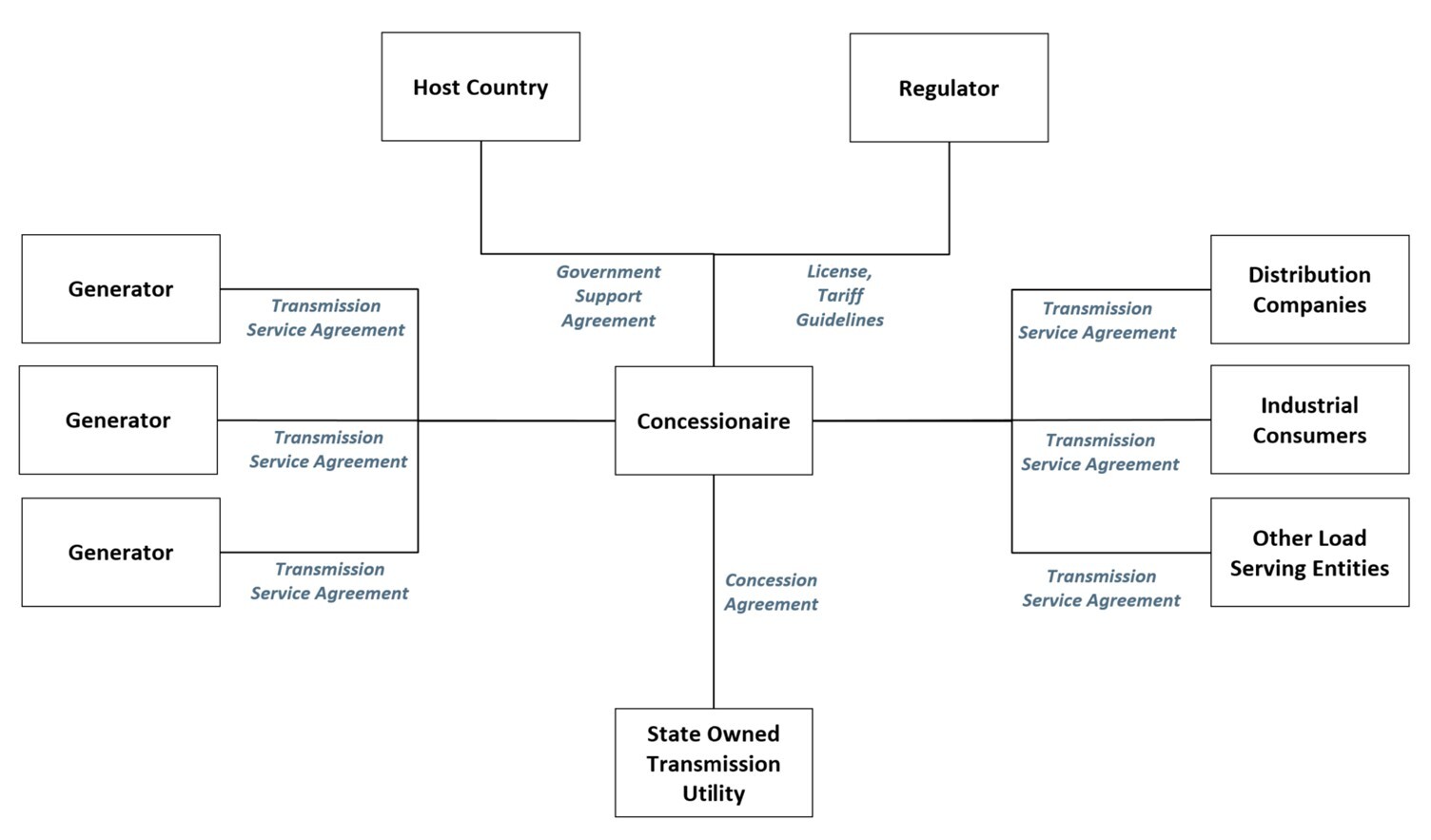

The participants in a concession and their contractual relationships are shown in the diagram that follows.

The above diagram assumes that the grantor does not also function as a single-buyer (the purchaser under all power purchase agreements) and the supplier to distribution companies, industrial consumers, and other load serving entities. If it does, then either the grantor may continue to serve that function or the concessionaire could assume that function by entering (i) into a bulk supply agreement with grantor (under which it would purchase the capacity made available by, and the energy generated by, generators from the grantor), and (ii) separate bulk supply agreements with the distribution companies, industrial consumers, and other load serving entities to which it supplies energy. Both approaches involve some complexities that are outside the scope of this article. For our purposes the important point is that these complexities exist but can be overcome.

As the concessionaire constructs and installs new equipment and facilities and those facilities become part of the transmission system, legal title to the new equipment and facilities vests in the grantor so that the grantor remains the owner of the entire transmission system during the term of the concession. If, for example, the concessionaire needs to acquire additional rights of way, easements, ownership interests, or leasehold interests in land to expand the transmission system, the concessionaire acquires those interests in the name of the grantor, and those interests become subject to the leasehold interest and access rights created by the concession.

The concessionaire will be responsible for operating and maintaining the transmission system. If the legislative framework provides that the holder of a transmission license is responsible for dispatching generation and balancing the system, then the concessionaire will be responsible for those functions. If the legislative framework contemplates that those functions will be performed by a separate transmission system operator, then those functions will be performed by the entity that holds the license to act as the transmission system operator. It is important to think about the transmission system operator role as being possible to separate from the role of investing in and maintaining the network, because some governments regard the TSO role as being strategically sensitive.

The concessionaire will recover its ongoing operations and maintenance fees from the use of system fees it charges for transmission. It will finance capital expenditures to upgrade and expand the transmission system with a combination of debt and equity. Equity will be contributed by the shareholders in the concessionaire or created through the retention of earnings by the concessionaire. The concessionaire will raise debt by borrowing from lenders or by issuing bonds or preferred shares. The concessionaire’s ability to raise capital in the form of equity, debt, and preferred shares is highly dependent on several factors. Of these, the most important are:

- how the concessionaire is regulated;

- how the buy-out payment (a payment that is payable by the grantor upon the expiration or termination of the concession in respect of the undepreciated portion of the investments made by the concessionaire) is structured; and

- how risks are allocated.

These topics will be explored in subsequent articles.

1 See Tonci Bakovic, Bernard Tenenbaum, and Fiona Woolf, Regulation by Contract – A New Way to Privatize Electricity Distribution?, 2003.