Overboarding by Public Company Directors—A Reference Guide

November 18, 2021

Outside board service can be helpful in grooming senior management, gaining experience or insight, and developing important business relationships. However, board service has become increasingly demanding and time-consuming; therefore, proxy advisory firms and institutional investors have placed limits on the total number of directorships certain individuals can hold at any one time – above which such directors will be considered “overboarded.”

For the following reasons, “overboarding” considerations require increased attention as public companies look to 2022:

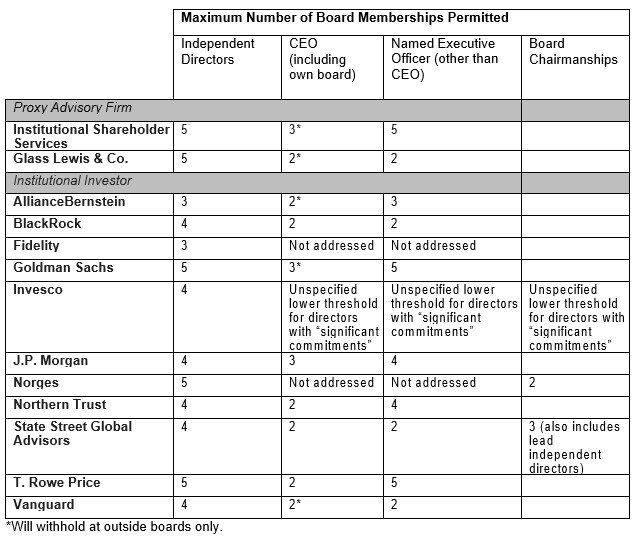

- Institutional investors are increasingly adopting their own voting guidelines. These institutional investor guidelines often deviate from the policies of Institutional Shareholder Services (“ISS”) and Glass Lewis & Co. (“Glass Lewis”). Accordingly, public companies need to look to the published voting guidelines of their major shareholders (as opposed to just the guidelines of ISS and Glass Lewis). By way of example, State Street Global Advisors’ voting guidelines state that it may withhold votes from any named executive officer (“NEO”) who sits on more than two public company boards, and against non-executive director nominees who sit on more than four public company boards. This policy is more restrictive than the voting guidelines of either ISS or Glass Lewis. As shown in the table below, ISS’s policy is that a CEO should not serve on more than three boards (including his or her own board), while other directors (including non-CEO executives) can sit on up to five boards. Glass Lewis’ policy is that inside directors (i.e., CEOs and other NEOs) should not serve on more than two boards (including their own boards), while outside directors should be limited to five boards.

- In response to calls for increased boardroom diversity – including the new required Nasdaq board diversity matrix disclosure – many public companies are actively looking to add new, diverse members to their board. When adding such members, in addition to independence considerations, public companies also need to consider the “overboarding” guidelines of ISS, Glass Lewis and their specific investor base.

Here is a table showing the current “overboarding” guidelines for ISS, Glass Lewis, and various institutional investors (as of November 2021).

Conclusion

It should go without saying that simply because a director exceeds the limits imposed by a proxy advisory firm or institutional investor does not mean the director is unfit or unable to serve effectively. Counting a director’s board seats is not a measure of director effectiveness. In addition, outside board service can be valuable, especially in grooming talent below the CEO level. Nevertheless, companies and boards need to consider not just their investors’ voting guidelines, but also the concerns giving rise to such guidelines – specifically concerns regarding the director nominee’s ability to dedicate the requisite time and attention to effectively fulfill his or her responsibilities to the company and the board.

Accordingly, action items for management, boards, and governance committees include:

- reviewing the overboarding policies of their largest investors and of the proxy advisory firms as part of their review of board composition, board refreshment strategies, and recruiting new directors;

- reviewing their corporate governance guidelines to determine whether to adopt or update company-specific overboarding policies;

- considering other time constraints of directors and potential directors that may adversely affect board service, including the individual’s full-time job, responsibilities at not-for-profit boards, responsibilities at privately held company boards, and time-consuming committee assignments or other board leadership roles at the company or on other boards (e.g., lead independent director, board chair, audit committee membership, etc.); and

- being prepared to discuss overboarding issues when engaging with institutional investors.