Private Investment in Transmission

January 21, 2022

By Ryan Ketchum and Chris Flavin. Ryan is a partner at Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP. Chris is Head of Business Development at Gridworks Development Partners, a development and investment platform principally targeting equity investments in transmission, distribution and off-grid electricity in Africa.

There is currently a need for significant additional investment in transmission on the continent of Africa. This need is unlikely to be met through the existing sources of funding for the sector.

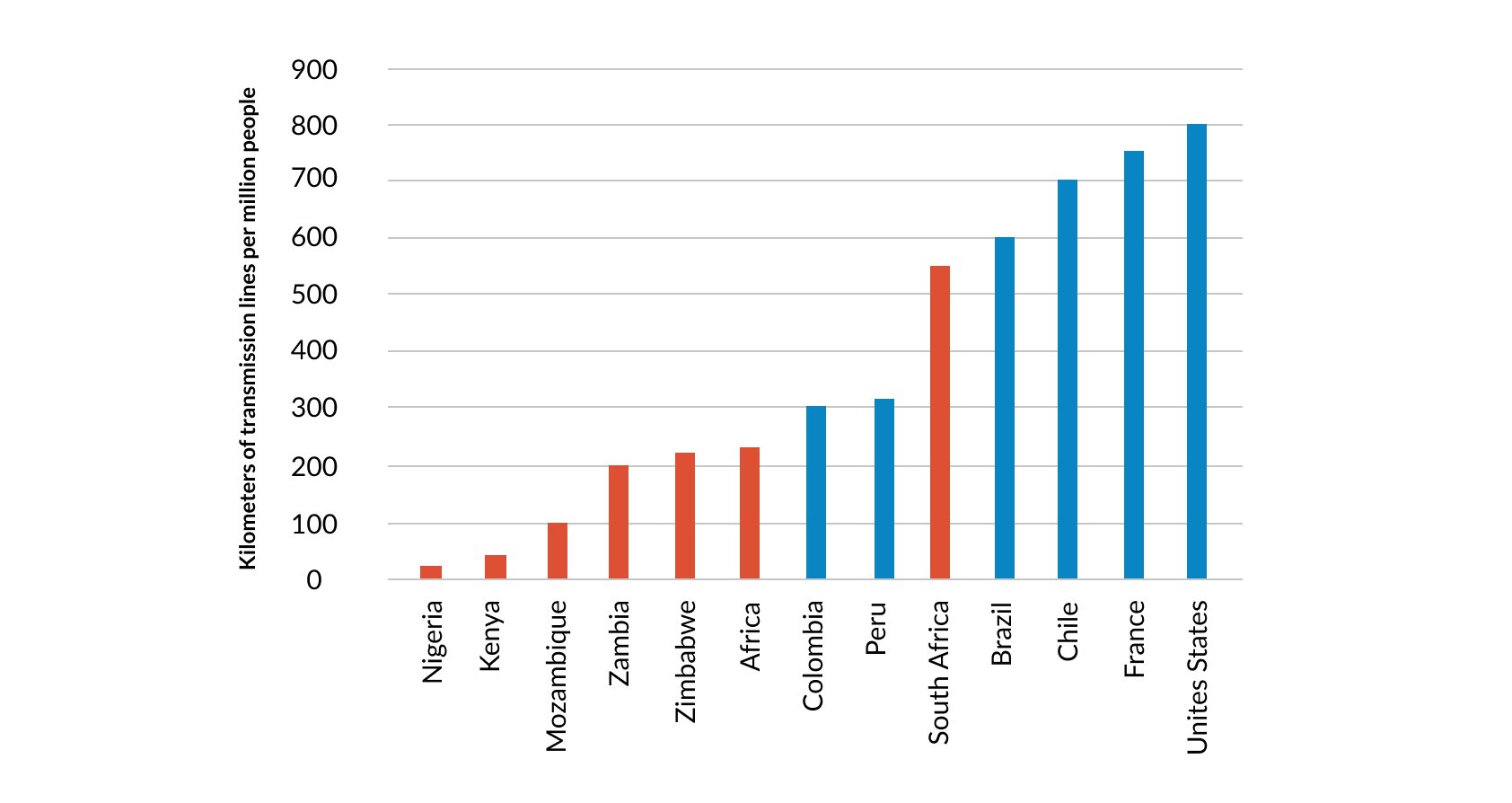

As things stand, 52% of people who live in Sub-Saharan Africa currently live without access to electricity.1 Investment in new power generation over the past few decades has not been matched with corresponding investment in electricity networks, and this is now a major constraint on increased access. Africa has fewer kilometers of transmission lines per capita than any other continent.

As well as the energy access imperative for transmission investment, it is also critical to economic development. Numerous studies have demonstrated the economic value of increasing investment in electricity transmission systems.2 Access to reliable and affordable power for businesses is critical for the industrialization of developing countries and suitable capacity on a well-maintained high voltage transmission backbone is a prerequisite to this that is missing in many countries.

Finally, transmission infrastructure is essential to support the transition towards energy systems that are less carbon intensive. Investment in grid stability is necessary to support an increased percentage of intermittent renewables in the generation mix, and a larger transmission network will be necessary in most countries to connect areas of high renewable generation potential with areas with demand. The investments Egypt made between 2014 and 2020 illustrate the scale of the investments that could be required to integrate renewable energy resources. Between 2014 and 2020 the Egyptian Electricity Transmission Company commissioned over 3,600 km of 500 KV transmission lines. At the end of 2020, the length of their 500 KV transmission system was 2.5 times its length in 2014. Much of this investment was necessary to connect new renewable energy projects in the south to load centers in the north.

The International Energy Agency has estimated that achieving Africa’s electrification ambitions will require investments of approximately $120 billion per year, “with the vast majority of those investments going to low-carbon and grid networks.”3 Source – Linking Up, pg. 9.

Source – Linking Up, pg. 9.

Historically, the vast majority of investments in transmission on the continent have been made by state-owned utilities. For the most part, these investments have been funded by government, or with support from government through sovereign backed loans from multilateral development banks. This source of funding for the sector has not kept pace with the need for transmission infrastructure, and the bottleneck created by this represents a major economic development challenge and a climate problem. Without additional sources of funding for the sector, Sustainable Development Goal 7 (access to affordable, reliable and sustainable energy for all), and 2050 net zero climate commitments set by governments will not be met. Growing pressure on African governments budgets, particularly in the wake of the Coronavirus pandemic, have compounded this problem as many nearer term projects that had been earmarked for government support have now stalled.

Until the 1990s, state owned utilities were responsible for investments in transmission in most emerging markets. That decade saw a wave of restructuring across Latin America, along with many members of the OECD, which led to new business models for developing and financing transmission infrastructure.4 At least one of these models – the independent transmission project model – was successful enough at decreasing costs and reducing project implementation risks that it has subsequently been employed in the U.S. and the U.K. even though the transmission systems of both countries are, by and large, privately owned networks. In the U.K., the Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (Ofgem) estimated that using that model resulted in cost reductions of between 23% and 34% in relation to approximately 3 billion Pounds of investment in transmission related to new offshore wind projects.5 In the U.S., a recent report estimated that competitive transmission development processes can be expected to yield cost savings ranging from 20% to 30% on average, when compared to non-competitive development by incumbent transmission owners.

In many respects it is not surprising that private funding has not yet been utilized for transmission in Africa to the extent it has in other continents. Investment in generation is usually considered to be easier to structure and organize and significant private investment in generation did not begin in Africa until the late 1990s. Agreeing roles and responsibilities between a private investor and state owned utility is more difficult with transmission assets which are often closely integrated with the existing network. Transmission networks are usually centrally planned and organized to a very high degree by the government or state owned entities and it can feel like a loss of control to open up the network and involve third parties for the first time, particularly for governments, which still often consider transmission infrastructure as strategically significant. However, in the current fiscally constrained economic environment, it is clear that the governments in Africa that can unlock new sources of funding for the energy sector will be the governments most likely to succeed in expanding electricity access, improving the provision of power to industry and improving sector sustainability. There are many transmission projects without funding at present which have the potential to build critical infrastructure with a clear accretive financial case. National development plans depend on this infrastructure being built, and the global energy transition relies on suitable network infrastructure existing in order to unlock renewable energy sources.

At least four different business models could be used to facilitate private investment in transmission infrastructure across most of Africa (and in emerging markets more generally). Those four business model are:

- whole of network concessions,

- independent transmission projects (“ITPs”), which are also known as independent power transmission projects,

- privatizations (a sale of shares by a government in a state owned utility or transmission company), and

- merchant lines.

These four models are described, in the most general of terms, below. In subsequent articles, we will examine some of these models and the issues they present, in more detail. As is the case with independent power projects, and public-private partnerships more generally, these models are flexible and can be tailored to better address unique needs, constraints, and challenges. As a result, the models described below should be taken for that are – archetype-like models that can be modified so that they can be implemented across a wide variety of circumstances.

Whole of network concessions

In a typical whole of network concession, the owner of the transmission system grants a long-term concession over the existing transmission system, typically for 20 to 30 years. The private investor awarded the concession is then responsible for operating and maintaining the existing transmission network and for financing and constructing new investments in transmission infrastructure in the service territory over the term of the concession. Although this model has resulted in significant investment by the private sector, significant loss reductions, and significant improvements in key performance indicators in countries outside of Africa, there has not been much experience with this model in relation to transmission in Africa. A few key challenges must be overcome before this model can be implemented successfully. These challenges are identified below.

1. Regulation

Network industries require significant levels of on-going investment. In addition, operations and maintenance costs are likely to vary significantly over the term of a typical concession as the network expands and connections to the network increase. As a result, it is not feasible for investors to bid an availability payment or use of system charge that will apply over the term of the concession. Instead, the business is regulated using cost of service or performance based ratemaking concepts. Both of these forms of regulation rely on periodic determinations of the regulated asset base (the quantum of investments made by a utility on which the utility earns a return and which are recovered by the utility by including a depreciation charge in the utility’s annual revenue requirement), the cost of debt, the cost of equity, and the cost of operations and maintenance that should be recoverable by the utility.

As a general rule, investors and lenders are reluctant to rely on an independent regulator to establish rates based on cost of service or performance based ratemaking concepts unless the regulator has an established track record of fairly balancing the interests of consumers and investors. Few regulators in Africa have had an opportunity to establish such a track record. The fact that rates paid by consumers are not cost-reflective in the vast majority of African countries significantly heightens perceived risks regarding the stability of regulatory frameworks and the practical ability of regulators to balance the interests of consumers and investors.

2. End of term payments

Because network industries require significant levels of on-going investment, the investments made by the private sector will not have been fully depreciated by the end of the term of the concession no matter how long that term is. As a result, the state owned utility (or the host country) will need to make a sizeable payment to the concessionaire at the end of the term (a buy-out payment). A state owned utility or host government could raise the capital required to make such a buy-out payment by entering into another concession at the expiration of the first concession and requiring the new concessionaire to pay an up-front concession fee that corresponds to the size of the buy-out payment owed to the first concessionaire. A state owned utility or host country could also raise the buy-out payment by issuing bonds or borrowing from other sources. In either case, the likelihood that the state owned utility or host government may not be able to close on such a transaction may be high enough – or may be perceived by investors and lenders to be high enough – to make it difficult for a concessionaire to raise debt financing.

It is worth noting, however, that similar issues have been successfully overcome in relation to concessions in the distribution sub-sector that were awarded in Sub-Saharan Africa, a sub-sector in which the same risks are present. So although this risk may be difficult to overcome, experience has shown that it can be overcome.

3. Expropriation and nationalization risks

Thirty-three whole of network concessions in the transmission and distribution sectors in 16 emerging market countries have been reversed through the termination of concessions, nationalizations, and expropriations.6 Although these types of events can in theory be policy driven and completed under a pre-agreed process which protects the legitimate interests of an investor on the one hand, and the government on the other, this is not always the case. Early termination is not usually the result of a successful concession arrangement and it carries significant risk for both the investors and the government. These experiences have caused investors to carefully consider a country’s political economy, how a whole of network concession may be perceived in that political economy, and a country’s long term level of commitment to such an arrangement.

Independent transmission projects

In contrast with a whole of network concession, an ITP involves the construction and maintenance of a single transmission line or a package of transmission lines. In emerging markets, these transactions are implemented under a long-term contract, generally between the state owned utility that is responsible for transmission and the (private) project company that is established to undertake the project. Such a contract may be known as a transmission purchase agreement or a transmission service agreement.

Unlike a whole of network concession, in an ITP the project company is not obligated to expand the transmission line(s) it will construct, own, and operate. As a result, the host government, regulatory authority, or state owned utility may conduct an auction to establish an annual revenue requirement or monthly availability payment. Although a portion of the annual revenue requirement or monthly availability payment that corresponds to the operations and maintenance expenses the project company will incur may be indexed, the majority of the annual revenue requirement or monthly availability payment will be fixed for the term of the project.

In order to support the ability of the project company to raise long term debt at attractive rates – which ultimately benefits consumers by lowering cost of the capital required for the project and thereby lowering the availability payment to the project company – the project company should be paid for the availability of the transmission line regardless of the quantity of power that flows over the line. In many cases, the auction that is conducted to select the investors is conducted by the regulatory authority, as is the case in Brazil, where the electricity regulator (ANEEL) conducts the auctions. Between 1999 and 2017 Brazil conducted 38 tenders for ITPs, resulting in the award of 211 projects with a combined length of over 69,000 km.7

Privatizations

A privatization by a sale of shares involves the sale of some or all of the shares in a state owned enterprise to private investors. In the context of privatizing a utility in the transmission business, it would involve selling shares in that utility to private investors.

This model has been adopted by many high-income countries, including the U.K., which privatized all of its transmission networks in three separate transactions in 1990. Experience with this model in relation to transmission in emerging markets is limited.8 Although there is much to recommend this approach, as is the case with a whole of network concession, the requirement for independent regulation and the perceived risk of expropriation or nationalization may render this option difficult to achieve in practice in many emerging markets. In addition, discussions with officials in many emerging market countries has shown that many countries are reluctant to implement a transaction that would, in their minds, result in a significant loss of control by the government over assets that play such a central role in the deliver of an essential service.

Merchant lines

Merchant lines are transmission lines constructed by private investors who seek to profit by transmitting electricity from areas in which the cost of power is low to areas in which the cost of power is higher. Many of these lines are dispatchable high voltage direct current lines.

Although several successful examples of merchant lines exist, some merchant lines have been adversely affected by the growth of the transmission systems they connect, which reduced or eliminated the opportunity to profit by arbitrage. In many emerging markets, the risk that organic expansion of the existing transmission system may reduce or eliminate the profits that can be generated by a merchant line is particularly high given that the networks are not fully developed and are likely to grow.

In addition, a host country would need to affirmatively elect to allow the owners of a merchant line to earn returns that are significantly in excess of the returns that would ordinarily be earned by a regulated network utility. For these reasons, we see merchant lines as an interesting business model that may be attractive in unique circumstances but is not likely to be attractive – to either investors or host countries – in most cases.

Which models are most likely to succeed in Africa?

For the reasons described above, our view is that widespread private sector participation in the transmission sub-sector in most countries in Africa is unlikely to arrive in the form of the privatization of existing state owned transmission utilities or merchant lines.

Whole of network concessions offer many benefits. They may be particularly attractive to countries that need to fund significant extensions, upgrades, and expansions of national transmission systems and would like to harness private sources of capital to fund those extensions, upgrades, and expansions. Whole of network concessions may also be attractive to governments that believe that a privately-owned concessionaire would be better placed to maintain and operate an existing transmission network, which would increase the overall availability of the system, improve the overall efficiency and utilization of the network, and thereby decrease costs to consumers on a per-unit basis.

While whole of network concessions offer many benefits, they also require host countries, investors, and lenders to overcome what can be significant issues in the context of many countries in Africa. Those issues include the three we highlighted above and some additional issues we will explore in a subsequent article.

In contrast, ITPs offer several advantages. Some of the principal advantages follow.

- The first two risks we highlighted in relation to whole of network concessions (economic regulation and buy-out payments) can be avoided altogether.

- It is more practical to raise capital for ITPs using project finance techniques than it is to capital for whole of network concessions using project finance. Fundamentally, project finance separates out the cash flows and the risks that are related to a particular investment from the cash flows and the risks that are related to other investments. Single transmission lines or packages of transmission lines offer much better opportunities to separate cash flows and risks than do whole of network concessions.

- Independent transmission projects allow countries to conduct competitive tenders in relation to discrete projects as the need for those projects arises. This means that countries can gain valuable experience in structuring projects and conducting tenders. Likewise, investors gain confidence as a country establishes a track record of conducting well-structured and transparent tenders, leading to lower costs for successive projects.

In part because of these advantages, significant investments have been funded using the ITP model. Over 50,000 km of transmission projects have been constructed using the ITP model in Brazil alone. Peru, India, Chile, and other countries have also successfully implemented these projects at scale. Significantly, the experience in these countries has demonstrated that ITPs are often implemented at a fraction of the anticipated cost. In Peru, for example, the capital cost of ITPs was, on average, 36% less than the expected cost. Brazil’s experience with ITPs resulted in similar cost reductions.

Given these factors, we view ITPs as a promising avenue for private investment in transmission in Africa, followed by whole of network concessions. In subsequent articles, we will examine some of the considerations that go into structuring both ITPs and whole of network concessions.

>>Back to Africa Projects > Private Investment in Transmission

1 See https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/people-without-access-to-electricity-in-sub-saharan-africa-2000-2021.

2 For a summary of various studies see Pfeifenberger and Chang, Well-Planned Electric Transmission Saves Customer Costs, June 2016, pp. 5-14. For a discussion of this topic in relation to Africa in particular see Power Africa’s Transmission Roadmap to 2030, a Practical Approach to Unlocking Electricity Trade, November 2018.

3 IEA Africa Energy Outlook, November 2019, pg. 10.

4 See Linking Up: Public-Private Partnerships in Power Transmission in Africa, The World Bank, 2017.

5 See Extending Competition in Electricity Transmission: Impact Assessment, 2016, by Ofgem.

6 See Rethinking Power Sector Reform in the Developing World, Vivien Foster and Anshul Rana, 2019, pg. 14.

7 Linking Up, pg. 39.

8 Id.